Christ's Presence in The Lord's Supper from a "Biblical" Perspective

A conclusion that I cannot help but arrive at based off of Scripture

In order to as clearly as possible define and explain what the Lord’s Supper actually “is” from within the pages of Sacred Scripture, I believe that Paul’s first letter to the Corinthian Church provides a great starting point. It not only serves as a great introduction to typology and opens the door for connecting some dots between aspects of the Old and New Testaments, but it also allows for the presence of Christ to be firmly established within the context of the Eucharist. In that letter, Paul mentions that by partaking in the bread and the wine at the Lord’s Table, believers are participating in—or communing with, depending on the translation—the body and blood of Christ (1 Cor. 10:16). Paul is clearly not speaking metaphorically here, at least not in relation to the fact that the Lord’s Table involves a special communion with Christ, because he then goes on to warn against sacrifices knowingly offered to demons since doing so would involve a person communing with or participating with them (1 Cor. 10:20). There would be no risk involved with offering sacrifices to demons or eating at their table if a communion with said demons was not possible or if the demons were not in some way present. Relatedly, if a participation/communion with demons is possible then so too is a participation/communion with Christ. Unless, of course, one is willing to think that the spiritual forces of darkness are more present and active than God Himself. Nevertheless, Paul reinforces the reality of one’s participation with Christ, and thus one’s experience of Christ’s presence, during the partaking of the bread and the wine in the following chapter.

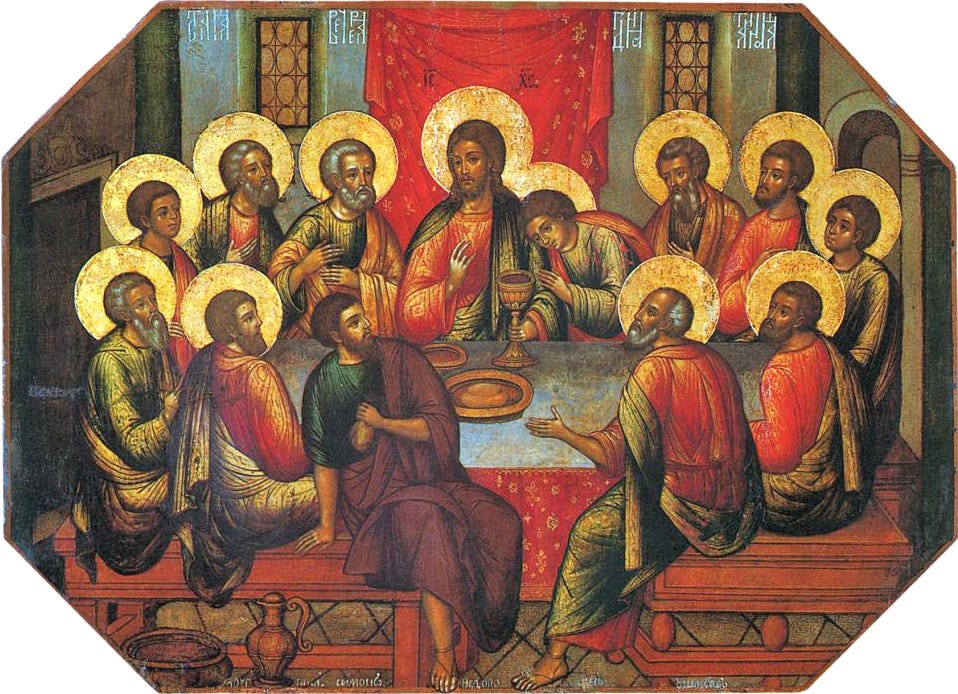

It is within the 11th chapter that we read Paul informing the Corinthian church that many of their members have brought weakness, illness, and death unto themselves due to their unworthy manner of partaking in Communion (1 Cor. 11:30). That unworthiness comes from being seen as guilty before the Lord and it seems that a significant reason their guilt bears such a heavy price is because God’s presence is amongst them when partaking in the Eucharist. Such a reality is apparently brought to the forefront by Paul through his recall of Christ’s words during the Last Supper:

“For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, ‘This is my body, which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’ In the same way also he took the cup, after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood.’”

1 Cor. 11:23-25

It is after these words of Christ’s are restated that Paul then explains why many of the members of the Corinthian church are suffering and dying. I can only assume from a plain reading of the text that such an ordering was intentional. Paul wanted the Corinthian church to think back on Christ’s sacrifice and to also dwell on the very words of the Savior, which include the infamous “This is my body” and “This cup is…my blood” language. He was pastorally attempting to lead them towards a conclusion that he was going to nonetheless state. Paul is redirecting the Corinthian Church towards the foot of the cross to remind them that they are eating the fruit of the new tree of life. Essentially, he was “showing them the work” in the same way that a math teacher shows the work and instructs his students on how to arrive at an answer to an equation so that they can move forward, solving similar equations in the future. Furthermore, I believe that a consideration of how God’s presence was detailed in the Old Testament additionally serves to reinforce this reading of this passage. While an extensive coverage of every single reference to God’s presence in the Old Testament would be possible, it would also extend the length of this writing to a ridiculous degree. So, I will instead focus on select readings from Exodus and 2 Samuel because they can provide an encapsulation of the teaching of God’s presence and its effects in a digestible length.

The long-story-short version of this discussion is that both Exodus and 2 Samuel show that God is present, especially amongst sacred things or places, and that an unworthy or inappropriate encounter with His presence can result in death. I want to dig in a little further than that surface level summary, however, so let us look some excerpts from Exodus 25 first:

“8 And let them make me a sanctuary, that I may dwell in their midst. 9 Exactly as I show you concerning the pattern of the tabernacle, and of all its furniture, so you shall make it. … 21 And you shall put the mercy seat on the top of the ark, and in the ark you shall put the testimony that I shall give you. 22 There I will meet with you, and from above the mercy seat, from between the two cherubim that are on the ark of the testimony, I will speak with you about all that I will give you in commandment for the people of Israel. … 30 And you shall set the bread of the Presence on the table before me regularly.”

Ex. 25:8-9, 21-22, 30

Verse 8 establishes that God’s presence was in the sanctuary and verses 21 and 22 show exactly where God’s presence was going to be physically located within said sanctuary. And the Bread of the Presence in verse 30 serves as another tangible reminder of God’s presence within the same location. Of course, God is an infinite, eternal being who cannot be wholly confined to any sole location, but as author of the universe He can make Himself present wherever He pleases in whatever way He pleases. His location on the mercy seat and the Bread of the Presence are two such instances of His purposeful placement and connection to tangible objects or places.

It must be noted that this is not the first time that God’s presence is tied to a physical place or physical elements, nor is it the first time that one’s behavior or apparel must be adjusted accordingly. One only needs to look back to the beginning of Exodus to read the story of the burning bush and see Moses commanded to remove his sandals due to being on holy ground (Ex. 3:5). What made that ground holy? Was it holy by coincidence or holy because God was in some way present? I think that the answer is obvious. This treatment of God’s presence as sacred and powerful is further reflected in Exodus 19 where, during the account of Moses and the Israelites’ encounter with God at Mt. Sinai, Moses is instructed to consecrate the people by having them wash their clothes (Ex. 19:10). Additionally, Moses is told to put to death anyone or anything, be it man or animal, that touches the mountain. In fact, they must be killed by stoning or by being shot with arrows to prevent anyone else from touching them (Ex. 19:12-13). Even the Priests, who were otherwise already set apart, were instructed to consecrate themselves or suffer the Lord breaking out amongst them (Ex. 19:22). It is also worth referencing the instructions given regarding the garments of the priesthood a few chapters later so that the sacred power of God’s presence can be further highlighted outside of the encounter at Mt. Sinai. In Exodus 28 Aaron and his sons are told to be brought out from amongst the Israelites to serve as priests. As part of their consecration, they are told that they will wear sacred garments made for them by the skilled workers of the nation. Those garments are made to explicitly give to the priests “dignity and honor” (Ex. 28:2) so that “they may serve [God] as priests,” (Ex. 28:4). Verse 43 doubles down on the importance of those garments when it reads: “Aaron and his sons must wear them whenever they enter the tent of meeting or approach the altar to minister in the Holy Place, so that they will not incur guilt and die,” (Ex. 28:43). The seceding chapters then go on to provide even further details regarding the sacrifices, washings, anointings, and so on that were all necessary for the proper and full consecration of the priesthood.

As you have probably pieced together from any of the aforementioned references, God’s presence is presented as so holy within the Old Testament that multiple preparations are typically required before coming into contact with Him, regardless of whether or not one’s intentions are seemingly pure. In very few places do we see this fact so obviously as we do in the story of Uzzah and his experience with the Ark of the Covenant in the sixth chapter of 2 Samuel or in the 13th chapter of 1 Chronicles where the same story is retold. As an ancient Israelite, Uzzah was assuredly aware of the multitude of rules and regulations surrounding all interactions with the Ark of the Covenant, the sanctuary, and other such things. He was presumably also someone who was filled with a proper amount of awe or respect—maybe love—for the Lord God Almighty. Regardless, when the oxen transporting the Ark stumbled and the Ark began to fall from the cart, Uzzah reached out to take hold of the Ark and was immediately struck dead by God (2 Samuel 6:6-7, 1 Chronicles 13:9-10). Uzzah violated the divine laws surrounding God’s presence and paid the ultimate price.

Now, all of that is not to say that the same exact rules, regulations, garments, anointings, washings, and preparations are required of us as believers within the New Covenant. We do not necessarily need to fear that an encounter with God’s presence will absolutely result in a fate like Uzzah’s. Hebrews 9 makes it abundantly clear that, as our High Priest, Christ fulfilled those requirements through His blood, having entered the holy places once for all (Heb. 9:12), and now appears in the presence of God on our behalf (Heb. 9:24). However, all of that is also not to say that God’s presence is something that should be treated lightly or taken for granted. Rather, it should continue to be treated with the utmost amount of fear and trembling. If you disagree, I would want to know where Scripture states that at some point between the Old Testament and New Testament accounts God’s presence somehow becomes less holy. Or I would ask you to point me towards a portion of Scripture that entirely separates any sort of righteous, spiritual power or presence from our Lord God Himself. There is inarguably a spiritual dimension and activity at play in Communion, or else there would be no consequence for an unworthy partaking or a warning against demonic participation. So, what sort of being or force is present? I say and ask all of that because as we look back at 1 Corinthians 11 with the previously listed passages from the Old Testament in mind, what seems to be the most logical conclusion regarding the cause of the ailments or deaths in relation to an unworthy partaking in Communion? To me, the answer is simple: Christ—the Son who is entirely and fully God—is present at the Lord’s Table in some manner.

A sort of plain text reading, one where we can take Christ’s words at the Last Supper somewhat literally and establish that Christ is present, seems to make the most sense of the passage. Why else would Paul want to remind the Corinthian church of Christ’s language and then use the verbiage of communion and participation himself? If there were any Jewish converts within the Corinthian church, they would have undoubtedly been familiar enough with the Old Testament writings and previous teachings on God’s presence. I would argue that a consideration of God as present in some manner during Communion would thus have been the default position of the Corinthian church. To be fair, perhaps it was not a position that was inherently held by everyone within that congregation. For instance, Gentile converts may have been unfamiliar with the concept of God’s presence or connection to tangible things or places. Although I would not be surprised to find that some of the pagan religions or practices from around that time contained analogous beliefs or practices. Nevertheless, Paul himself would have been writing with such a precedent of presence in mind so such a conclusion would have been what the apostle was directing the congregation towards, regardless of their prior religious backgrounds.

Outside of that passage from 1 Corinthians 11, Christ being mysteriously present in Communion ties into the sensory language used in other parts of Scripture. Psalm 34:8 tells us to “Taste and see that the Lord is good.” Song of Solomon is rife with experiential language and can be interpreted as an allegory for the believer’s relationship with God, in addition to being read as a celebration of love and intimacy between two people. Christ, apart from his institution of the Lord’s Supper as recorded in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, additionally tells his audience in the sixth chapter of John’s Gospel:

“Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you. 54 Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day. 55 For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink. 56 Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him.”

John 6:53-56

Despite occurring long before His institution of Communion, based on the surrounding context it is clear that Christ is being intentional with his use of sensory, experiential language and that He is most likely talking about the future practice. He is answering a crowd of people who are asking Him for more bread following His feeding of the five thousand. And He begins this portion of Scripture by calling out their ill intentions and urging them to cast off their base desires and instead crave the “food that endures to eternal life” (Jn 6:27) which is of course a reference to Himself. While it is assuredly true that Christ is generally referring to the act of following Him, the language is too specific to not be also referring to the practice of Communion in some sense. Take for example how Christ calls himself the “true bread from heaven” (Jn 6:32), “the bread of life” (Jn 6:35), and then specifies that “the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh” (Jn 6:51). Verses 53-56, which have been previously referenced above, serve as a culmination of sorts to this dialogue. The reactions of a number His disciples—many are quoted as stating that “This is a hard saying; who can listen to it?” (Jn 6:60) and many are also reported as turning their backs on Christ and no longer walking with him as a result (Jn 6:66)—further cements the intention and impact behind Christ’s words. Christ was relaying to them a difficult concept, and an especially challenging one at that. Not only was He advising them that He was the exclusive, singular way of salvation, He was also speaking in a way that would have been off putting to a presumably majority Jewish audience. A heavenly bread that is more sustaining than the manna their forefathers survived on? Eating the flesh of another human being? Is not every reference to cannibalism within the law and the prophets a curse? (Lev. 26:29; Deut. 28:53-57; Jmh. 19:9; Lam. 2:20, 4:10; Ezk. 5:10) It does not need to be stated, but I will anyways: Christ knew what He was saying and He knew the connections that a primarily Jewish audience would make. Christ’s knowledge and foreknowledge is then another concept which helps in our understanding of this passage and its connection to the Lord’s Table.

The miracle of water to wine at the wedding of Cana establishes a precedent of Christ’s words and actions connecting to future events, particularly His death and the salvific nature of His blood. When His mother, Mary, comes to Him and says, “They have no wine,” (Jn. 2:3) Christ replies with “Woman, what does this have to do with me? My hour has not yet come,” (Jn. 2:4). At first glance this almost appears as a somewhat tense interaction between mother and son wherein the former must prod the latter into acting. However, it must be remembered that as Lord God of the Universe, Christ did not need prompting by His mother nor was He answering with any sort of disrespect or intent to argue. Rather, what is happening here is Christ’s glimpse into His own future, a future which He had been intimately aware of since before the foundations of the world. The use of the word “hour” is what keys us into this particular reading of Scripture because that word, within John’s Gospel, is used exclusively in reference to Christ’s death (Jn. 7:30, 8:20, 12:23, 13:1). At that wedding, Christ was seeing how His own blood would be spilled like wine to cover the sins of the world. So, in His reply to Mary, Christ was, in a sense, saying that the wine He was providing was not yet from the fountain that was His own body. It was wine—good wine, at that (Jn. 2:10)—but it was not the eternal, saving wine that would one day flow from Immanuel’s veins. Nonetheless, Christ saw the cross at the wedding in Cana, and thus it is fair game to assume that Christ had His death in mind at other times amidst other miracles and during other conversations as well. To suggest otherwise would be to say that at certain points of His ministry Christ was simply unaware of what He was doing and was oblivious of the joy that was set before Him as He marched towards the cross.

Hopefully you can see why the miracle at Cana is so important in understanding the passage from John 6. Granted, the exact wording of “this hour” or “the hour” is not specifically present, but that does not negate the facts of God’s omniscience and Christ’s awareness of where His life was heading. The connection between Christ’s language of eating His flesh and drinking His blood can be connected too easily and too plainly to not be in reference to His eventual institution of the Lord’s Supper and His death on the cross to some degree. Again, pointing towards Communion is not necessarily the sole intent of John 6 but it is at least one of the intents.

Furthermore, the experiential and sensory language in the New Testament passages regarding Communion connects to the various types and precursors of Christ that are scattered throughout the Old Testament. To assist in understanding how we can identify these types and precursors, we can once again return to Paul and his first letter to the Corinthian church. There he writes:

“For I do not want you to be unaware, brothers, that our fathers were all under the cloud, and all passed through the sea, 2 and all were baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea, 3 and all ate the same spiritual food, 4 and all drank the same spiritual drink. For they drank from the spiritual Rock that followed them, and the Rock was Christ.”

1 Cor. 10:1-4

Per the words of the apostle, we are to understand the rock at Meribah as Christ. The parallel becomes even more striking—pun intended—when we see compare the two interactions involving the rock at Meribah as written in both Exodus 17 and Numbers 20. In the former, Moses is instructed by God to strike the rock in order that the people of Israel may have something to drink. In the latter, Moses is instructed to merely speak to the rock so that the people of Israel may once again drink, but Moses acts out and strikes the rock twice. As punishment for his disobedience, Moses is barred from accompanying the people of Israel into the Promised Land (Num. 20:12). Moses’ disobedience, specifically his lack of belief and disregard for God’s holiness, was immediately deserving of punishment, especially as the leader of the people of Israel who was to set a righteous example. However, Moses’ sin becomes all the more egregious, and his punishment all the more deserved, when one considers the connection that Paul makes. Simply stated: the rock was Christ. Moses’ first strike was thus a preview of Christ’s once for all death that would one day provide His salvific blood (Heb. 7:27). Yet, by striking the rock again in Numbers 20, Moses was striking Christ twice and declaring that Christ’s one time sacrifice at Calvary was not, and would not be, enough to provide for the Lord’s children. Regardless of Moses’ error, God still gave His people drink and, per the words of Paul in 1 Corinthians 10, by doing so they partook in Jesus Christ. Paul also makes a direct reference to spiritual food and the provision of manna from Heaven during the Exodus narrative is obviously the food that Paul is referring to. We could even look back at John 6 and see Christ make a comment regarding the manna provided to the Jewish forefather and then state that He was the true bread from Heaven (Jn. 6:58). The relationship between Christ, the manna, and the water from the rock is unmistakable.

We can apply a similar methodology, one where we repeatedly bounce between the Old and New Testaments, to identify the other types of Christ and precursors to the Lord’s Table. We have the tree of life with its fruit which gives eternal life (Gen. 3:22) and the tree at Calvary upon which Christ was crucified. Christ becomes the cross’s fruit and it is by eating His flesh that we have eternal life (Jn. 6:51,54). We also have the bread and wine that Melchizedek offers to Abraham as a blessing and source of sustenance (Gen. 14:18). In fact, Abraham then offers Melchizedek a tenth of everything he had in response to said blessing (Gen. 14:20) so it was immediately understood as a holy, priestly thing. Sure, I suppose it is possible that the bread and wine offered by Melchizedek are not related to Christ and Communion in any way, but if that were legitimately the case then why would a direct connection between Christ and Melchizedek be made in Hebrews 7?

1 For this Melchizedek, king of Salem, priest of the Most High God, met Abraham returning from the slaughter of the kings and blessed him, 2 and to him Abraham apportioned a tenth part of everything. He is first, by translation of his name, king of righteousness, and then he is also king of Salem, that is, king of peace. 3 He is without father or mother or genealogy, having neither beginning of days nor end of life, but resembling the Son of God he continues a priest forever. … 11 Now if perfection had been attainable through the Levitical priesthood (for under it the people received the law), what further need would there have been for another priest to arise after the order of Melchizedek, rather than one named after the order of Aaron? 12 For when there is a change in the priesthood, there is necessarily a change in the law as well. 13 For the one of whom these things are spoken belonged to another tribe, from which no one has ever served at the altar. 14 For it is evident that our Lord was descended from Judah, and in connection with that tribe Moses said nothing about priests.15 This becomes even more evident when another priest arises in the likeness of Melchizedek, 16 who has become a priest, not on the basis of a legal requirement concerning bodily descent, but by the power of an indestructible life. 17 For it is witnessed of him, “You are a priest forever, after the order of Melchizedek.” Heb. 7:1-3, 11-17

God, as the grand author of Scripture, appears to be guiding us towards certain conclusions intentionally. I would argue that He desires for us to see Melchizedek and his gift to Abraham as a precursor to Christ and His gift of Communion to the Church. And there are other types of Communion that I believe God wants us to have in mind as well! Let us consider the “cake baked on hot stones and jar of water” that are gifted to Elijah to empower him (1 Kgs. 19:4-8), the burning coal given to Isaiah that atones for his sins once it touches his lips (Isa. 6:6-7), and/or the scroll given to Ezekiel to eat before he is sent to testify to the Jewish people (Ezk. 3:1-4). In each of those instances, in addition to the previously mentioned passages, there are levels of sensation and experience of both the physical and spiritual worlds.

Whether it is the fruit of the tree of life, the bread and wine, the baked cake, the manna, the water, the burning coal, or the scroll that was as sweet as honey, God stimulates the senses of the person partaking so that they may, again, “taste and see that the Lord is good,” (Ps. 34:8-10). He knows that we as human beings are both spirit and body, and so He meets us where we are at and stimulates both aspects of ourselves. And, if He does so in those circumstances, why would He treat His own Table any different? I think that Paul’s wording of “spiritual food” and “spiritual drink” is of particular relevance here because it further reinforces how we are to not view the Lord’s Table any different.

While I am by no means an expert in Greek—I would not even call myself an amateur at Greek—I do have some baseline access to the language through Logos and the word that Paul uses in 1 Corinthians 10 to describe the food and drink of the Israelites is πνευματικός, pronounced pneumatikos, which, when translated to English, means “non-carnal; ethereal; spirit; supernatural; regenerate; religious; spiritual.” That last word “spiritual” may catch your eye because it is the word used in nearly every single Biblical translation of 1 Corinthians 10:3&4 except for, from what I can tell, the Aramaic Bible in English Translation which translates “spiritual food” and “spiritual drink” as “food of The Spirit” and “drink of The Spirit”, respectively. Either way, it seems to me that it is impossible to dispute the fact that the water from the rock at Meribah and the manna provided to them in the wilderness were channels through which the Israelite people spiritually experienced Christ. God was not literally, locally present in the water or in the manna, but He was nonetheless present in a spiritual manner. And, I know I have posed the question before, but why would the situation be any different when it comes to Communion?

Before I fully conclude, I understand that there may still be a lot of hesitancy with accepting Christ’s presence within the Eucharist. As someone who comes from an Evangelical, Non-Denominational, generic Baptist background, it is admittedly a concept that I would shrug off, accuse of being “too Catholic,” or just completely ignore for no real reason, so I can relate to feelings of hesitation. However, I also realized that I was always, without fail, reading the text with that sort of mindset ingrained within me. I never approached Holy Scripture without a voice in my head that repeatedly told me “it is only a symbol, it is just a memory, there is nothing to it” and so on. Honestly, it was not until the last year that I realized I was approaching the text with such a bias, and that my bias was preventing me from fully understanding God’s Word. And I focus so intently upon 1 Corinthians 11:17-34 because that was the passage that opened my eyes to my bias. Now, I do not mean to accuse anyone and everyone of bias if they do not read Scripture in the same way that I do, but I do wholeheartedly want to know how anyone can read that passage from Paul’s letter and conclude that there is zero spiritual aspect to Communion.

To me, a spiritual aspect is undeniable. As I stated towards the very beginning of this piece of writing, Paul would not warn against communion or participation with demons unless it is possible to do so. And, if it is possible to commune or participate with spiritual forces of darkness, it must also be possible to commune or participate with spiritual forces of light. With that said, if we can interact with the spiritual forces of light, it must certainly be with THE spiritual force of light, the being who created light itself. If it was a mere angel we were communing with, we would be cautioned against it entirely or else we would easily fall into making a god out of a fellow servant (Rev. 22:8-9). Plus, without it being Christ Himself who is present within the elements of Communion, and rather it being just some vague, random “good” spiritual thing, then we do not have Christianity but instead we have some type of weird spiritual gnosticism.

And, again, I think it is obvious that is not a vague spiritual entity or force we are interacting with at the Lord’s Table; it is Christ!

When we then factor in the rest of Scripture—the whole Counsel of God—Christ’s spiritual presence in Communion becomes more probable and less ridiculous. In my opinion, it becomes beyond probable… it becomes undeniable. As seen through the Old Testament accounts and types a special, spiritual encounter with Christ’s presence was the standard way in which humanity experienced Him prior to His incarnation. And now, in a post-resurrection world, one wherein Christ is locally present at the right hand of the Father (Heb. 1:3, 1 Pet. 3:22), a spiritual encounter through the Eucharist is how we continue to encounter Him. Yes, God is omnipresent, He fills heaven and earth (Jer. 23:24), and there is no where we can go without God’s presence. But! He is especially present at His Table.

Thanks for reading.